Uplifting, inspiring, empowering movies for female viewers that promote the advancement of women’s rights aren’t typical theatre fare, but this is precisely what the newly released independent film, Call Jane, delivers. Inspired by true events, it tells a story from the fight for women’s reproductive rights and celebrates women working together, collectively, as part of that fight.

The film, released in October, features women on camera, of course, but behind the scenes as well. Interviews with the filmmakers make it clear there was a commitment to female creators — from the shooting and directing to the music.

During the film’s international premiere in February, Call Jane’s director, 60-year-old Phyllis Nagy, explained: “We went out of our way to find women who could front the departments… It is so rare in America to find predominantly female crew, especially heads of department” (all the film’s heads of department were women). The screenplay was written by Hayley Schore and Roshan Sethi. Its cinematographer was Greta Zozula and its music supervisor, Isabella Summers.

Even its soundtrack foregrounds women. As Nagy told the Mill Valley Film Festival audience after a screening of Call Jane: “I want work largely by women of the period who were important, who were sometimes creating activist music.” In this vein, the film ends with Let the Sunshine In by Jennifer Warnes.

Call Jane is based on the story of a real collective of women called the Jane Collective, formed in 1968 in Chicago, who helped women and girls access safe, affordable abortions at a time when abortions were illegal in the United States. The movie ends in 1973 when the US Supreme Court Roe v. Wade ruling conferred the right to abortion in the United States, and the collective was subsequently disbanded.

At a press conference for the film, Nagy said:

“I had very little awareness of the real Janes when I came to the project and I think lots of women in America don’t have an awareness of them, which is a shame — and which doesn’t speak well to our education, right? But the real Janes were a group of college students, mostly, and activists that were almost accidentally formed, as this organization is in the film. They were an abortion referral service for a long time, using real doctors but also some not-real doctors. And then eventually they did learn to do the procedure themselves. And when they did learn that they were able to provide abortions for the women who really couldn’t afford it most: black women, women of colour, poor women, which they couldn’t do before that time.”

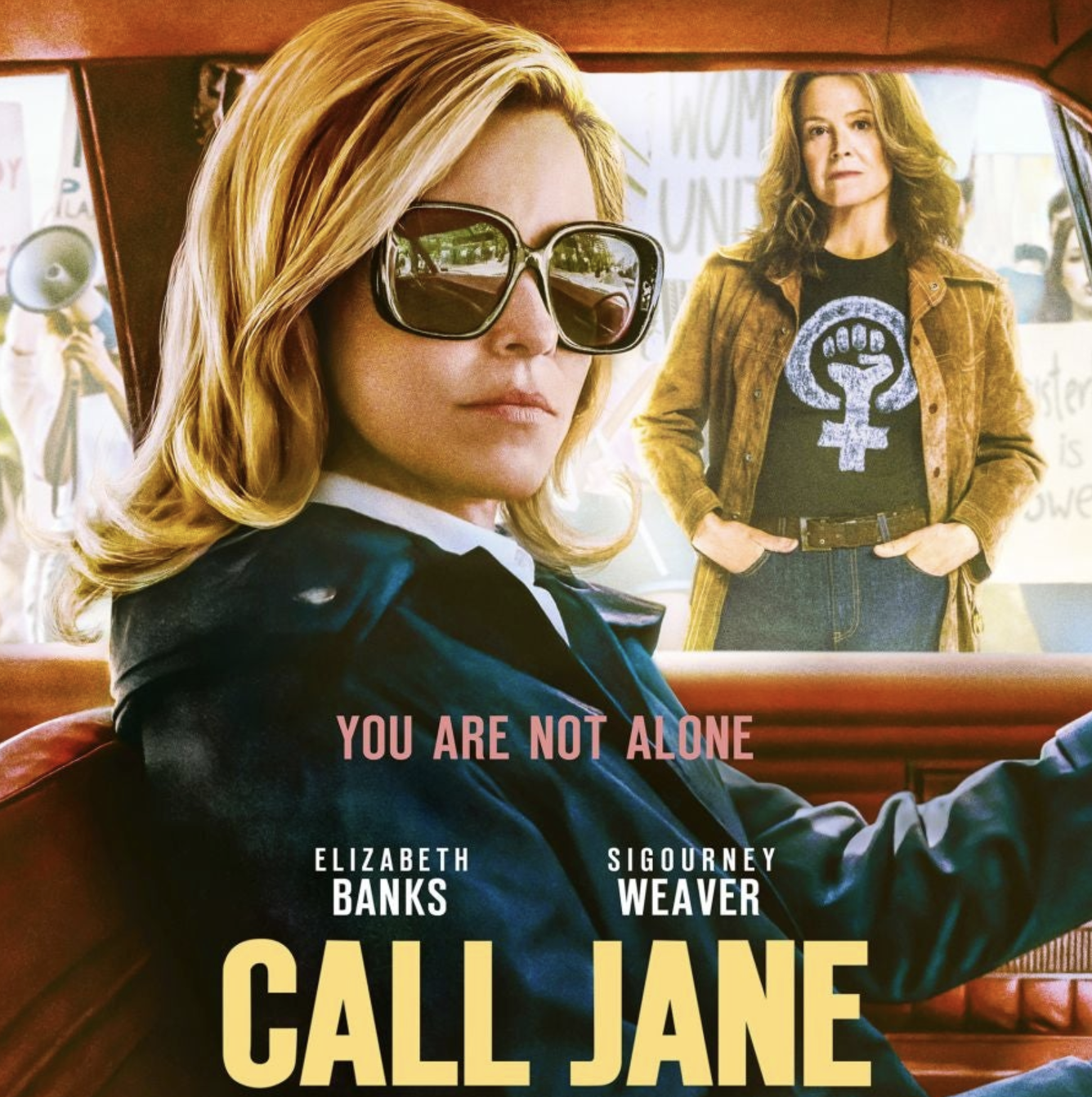

Call Jane’s story follows Joy, played by 48-year-old Elizabeth Banks, a traditional housewife and mother who needs to terminate her second pregnancy due to a life-threatening heart condition. According to her doctor, she has a only 50% chance of survival if the pregnancy is not terminated. When an all-male hospital board denies her request for a termination — the first solution suggested by her doctor — he suggests she plead insanity to receive a special dispensation. A doctor’s receptionist advises her: “Just fall down a staircase. It worked for me.” In desperation, Joy very nearly does throw herself down her staircase.

In the street, Joy finds a flyer for a clandestine women’s collective that secures abortions for women and girls in need. Following the successful termination of her pregnancy, Joy tells her husband and teenage daughter that she miscarried. Three days after the pregnancy is terminated, the woman who leads the collective, Virginia (played by 73-year-old Sigourney Weaver), calls Joy to check up on her. Upon discovering Joy is fine, Virginia asks her for a one-time favour: to drive a young woman to the clinic, as her regular driver is unavailable. Joy drives the young woman, after which Virginia says to Joy, “Well done, Jackie O” and gives her information about the collective’s next weekly organization meeting. Joy attends this meeting and becomes increasingly involved with the collective.

Joy begins assisting the collective’s abortion doctor, Dean, as a nurse of sorts, comforting women through the process. Soon, she takes an interest in medicine and the abortion procedure itself, and Dean allows her to assist him by administering shots. When Joy discovers that Dean does not have a medical license, she realizes she could learn how to perform the procedure herself, under his training and supervision, and start helping women. The collective had never lost a patient, and so Virginia was initially hesitant to allow Joy to perform the procedure without Dean. Joy manages to convince her, and Virginia tells her, “Okay, you get one shot.” While Joy performs the procedure Virginia acts as her nurse, holding the patient’s hand.

Dean charges the collective $1000 per procedure, a fee few women (or girls) can afford. Virginia replaces Dean with Joy, allowing the collective to lower the cost for women and girls seeking abortions.

Joy’s involvement with the collective puts strain on her marriage, as her husband is less than supportive and feels angry about having to make his own dinner, so she decides to take a step back. Before leaving, Joy tells the collective’s women (referred to as “Janes”) she will teach the procedure to whoever wants to learn. Then she will stop performing abortions but will continue to assist the collective through fundraising efforts, soliciting support from private donors.

We learn that 12,000 abortions were performed through the collective and not a single woman was lost. The film ends with a celebratory party for the collective in 1973 — abortion has been effectively decriminalized by Roe v. Wade, and Virginia says: “We’re shutting down because we’re redundant.”

Beyond the historical importance of telling women’s stories in the fight for reproductive rights, Call Jane provides a female-centric story rarely seen in film. Most of the lead characters are female and the two leads are over 40, unfortunately remarkable as we still rarely see women on film past their sexual prime. Call Jane passes the Bechdel test with flying colours, featuring female characters not only speaking to one another, but modelling congeniality and affectionate relationships among women, including intergenerational ones. Call Jane shows women what collective efforts can achieve.

Even the filmmaking process was unique — shot on film with a single camera in 23 days, technical and time constraints meant the mostly female filmmaking crew needed to be especially well organized. In an interview, Nagy explains:

“We had very little money to make a period piece and no time to produce it. We had to be quite regimented and planned everything while also leaving room for the usual things that happen all the time on set. So that was very challenging. The schedule was challenging.”

Call Jane’s website doesn’t advertise merch, but instead encourages women to “be a Jane” and “make your voice heard in today’s movement.” At the end of the day, Nagy believes the film is a “meditation on choice,” a pivotal point to remember in today’s climate, wherein bodily autonomy and freedom is so hotly debated.

Back in February, a journalistasked Nagy how women’s reproductive rights have evolved since the time depicted in Call Jane, she said: “We’re about to see a rollback on the protections of Roe v. Wade, perhaps not all at once, but gradually. We’re in very, very bad shape in terms of that.” Call Jane offers an important reminder of where we might end up if we allow our hard fought for rights to slip away.

Alline Cormier is a Canadian film analyst and retired court interpreter with a B.A. Translation from Université Laval. In her second career she turns the text analysis skills she acquired in university studying translation and literature to film. She makes her home in British Columbia and is currently seeking a publisher for her film guide for women. Alline tweets @ACPicks2.