When Stranger Things arrived on Netflix, I could not believe that a show for me and about me could possibly be enjoying such mainstream success. How could they have created a series about and for me and my friends — a bunch of geeky, unpopular, D&D-playing boys born in 1972, the year the fewest Anglo Americans have been born since 1945?

We all know the answer: some of our fraternity of socially unskilled boys who brought their Commodore 64s to the middle school science fair became the aristocracy — the royalty of the tech billionaires and millionaires who hold vast economic and political power in our society. The kids who were once bullied and mocked for their preference for online over in-person communication now sit atop a social system that has amplified the power of online communication, seeking to wholly subordinate in-person human interaction to it.

In other words, however outlying or bizarre our teenage subculture and the adult subculture it grew into, my powerful contemporaries in the interlocking worlds of big tech and entertainment are now shaping our social norms, our aesthetics, and values.

In 2008, I attended a workshop in Toronto, hosted by the Latin America Research group, wherein York University Cultural History professor Anne Rubenstein offered one of the most important observations I have ever heard about patriarchy and its perpetuation: systems of male domination are constantly staging a “crisis of masculinity.” Central to the hegemony of masculinity is the sense that it is constantly in crisis and under attack.

We see this writ small in so many abusive family dynamics: a male abuser’s power is total, precisely because his job and his family — even he himself — seem moments away from total collapse. By making himself and his masculinity the crisis his family is constantly managing, he can not only blot out the power of other members, but can blot out their point of view. By making it necessary to imagine the world through his eyes — out of fear that not governing oneself by his needs and desires will cause some kind of catastrophic explosion of poverty, violence, and social dislocation — the abuser can erase the needs, experiences, and perspectives of those around him

At the political level, our society stages endless moral panics about young men being too violent, too effeminate, too poor, too weak, too hirsute, too clean-shaven, too slovenly, too fashionable, etc. Again and again, it turns out that the thing we thought was going to destroy masculinity five minutes ago turns out to be a new kind of masculinity, which, in turn, is under threat.

We dateless, sedentary, RPG-playing, video-gaming boys were certainly on the list of threats to the masculinity of our day. Tabletop role-playing games like D&D were, according to popular opinion, making us too physically unfit, unable to take a punch, lousy at sports, and unsuccessful with women. At the same time, it was making us too violent, too murderous, and likely to join a Satan-worshipping street gang.

To understand the madness of today’s gender orthodoxy — one largely fashioned by men of my generation and subculture — we might want to think about the other putative threats around which the 1980s “crisis of masculinity” was organized.

One of the images most emblematic of coming of age as an Anglo American boy in the mid-80s was the Penthouse “lesbian” pictorial. Publishing photos of surgically-altered, airbrushed bodies of porn stars engaged in activities completely unrelated to actual lesbian bodies or sex but staged solely for the male gaze was a stroke of financial genius, no doubt. But its repercussions have turned out to be devastating.

I will never forget those first images of “lesbian” porn in Penthouse. They are as inextricable from my process of coming of age as my first heterosexual encounter in which I got to see and touch a real woman’s breasts up close. Largely because of simple luck and female generosity, the interval between seeing that first pictorial and touching my first real breast was a mere five years. But for many RPG and computer geeks of my generation, that interval was 10 years — even 20. Some are still awaiting that encounter, with increasing impatience.

Whereas older men tutted at these penis-free photo spreads, viewing them as being unmanly in that they did not depict penetrative sex, the holy grail of patriarchal sexuality, the retort among their growing group of fans was that this kind of pornography was actually the only truly heterosexual porn, as watching porn containing male bodies was in some sense homo/bisexual because it demanded its viewers appreciate some aspect of the sexualized male body. The biggest fans of this new genre of pornography began to turn up their noses at regular straight porn as “gross” and “gay” with its depiction of men’s penises ejaculating.

It is also beginning in the mid-1980s that we see conventionally attractive male porn stars like John Holmes replaced with the likes of Ron Jeremy and other troll-like, porcine leading men. Similar to what was expected of consumers of “lesbian” porn, these audiences were not asked to believe that the women performing sex acts on camera were experiencing either attraction or enjoyment. If dateless young men in basements were to have an audience identification character, it needed to be someone as ugly, as unlovable and repugnant as they understood themselves to be.

This question of audience identification foregrounds for us the potential meanings of the lesbian porn. If the viewer were to situate himself in the scene he saw before him, it was in one of two positions: (1) director — the unseen voice of command ordering women to perform sexual acts on one another, whose authority supersedes their own consciousness in commanding their bodies irrespective of desire or (2) one of the women, at once unimaginably beautiful and hypersexual, yet devoid of free will.

~~~

There is something shameful about being part of the group responsible for 96 per cent of murders and 98 per cent of rapes that take place in our society. As a result, expressions of fraternity and male solidarity often involve us exculpating our gender, as a whole, of its propensity for sexual and gender-based violence.

Louis CK was highly perceptive in observing that the 1980s offer us one of the best metaphorical expressions of this discourse in The Incredible Hulk live action show starring Bill Bixby and Lou Ferigno. The idea is that the Hulk exists within every man — that within each of us is a violent, non-verbal monster, consumed with destructive impulses, so monomaniacal in his rage that he ceases to possess free will. CK suggests that the end of each episode, when Dr. David Banner wakes up with a blacked-out memory, surrounded by a scene of wanton destruction and dead bodies of people possibly known to him, packs up his satchel and catches a bus to the next town, is every man’s post-sexual encounter experience.

The Incredible Hulk, weekly required viewing for my generation of D&D geeks, features Bixby’s characterization of Banner as a guilt-ridden, mild-mannered, politically progressive, socially retiring gentlemen, further underlining the fact that a mild manner and good politics — even the embrace of feminism — can not kill the Hulk within.

In an inversion of the Edgar Rice Borroughs Tarzan narratives, which argued that the sexual honour and decency of the Anglo male could not be destroyed, even in jungles of Darkest Africa, The Hulk made the opposite case: there exists within all of us this violence that no veneer of civilization can fully cover. Curiously, Banner never thinks of killing himself. He will travel from place to place, leaving destruction in his wake but always believes he deserves another chance so long as he is looking for a cure for this curse.

If every generation has a Platonic ideal of hyper-masculinity, my generation’s is the Hulk. And in fact, the hyper-muscular, green-painted, roided-up body of Ferigno shares with the Penthouse lesbian not only a hyper-sexualized, hyper-sexed body, but the complete absence of free will.

It is out of this understanding of the male will that an oath arose. During my 20s and 30s, I noticed that potential new male friends would, after an enjoyable evening of drinking, present me with the “Dead Hooker” loyalty oath. Lampooned and nodded-to in films like The Hangover, an all-too-common way for one’s new male friends to let one know that a new threshold of male intimacy had been crossed was to assure you that if you woke up with a dead sex worker in your bed and needed assistance disposing of the body, they would assist you and do so non-judgementally.

These declarations are always made both tongue-in-cheek and in deadly seriousness. Whether they have meant it or not, we all know that millions of Anglo American men have promised each other that they will help their male friends and acquaintances dispose of the raped and murdered bodies of prostitutes. And through their ubiquity, these declarations have come to be seen as expressions of a man’s loyalty and decency, not his shared depravity and propensity for misogynistic violence.

Of course, this kind of talk did not come out of nowhere. A key feature of patriarchy’s love and use of team sports is the idea that a desirable young woman is, in a sense, the ball in a team sport. The woman’s family, male relatives, teachers, priest, and others with a protective responsibility towards her are on one team, focused on protecting her from potential suitors. On the opposing team are a younger man and his friends who will pool and share advice, and lend vehicles, clothes, money, information… Whatever it takes for a young suitor to win that beautiful woman over.

In past patriarchal societies, the woman’s relatives and protectors used to be a lot more mobilized, a lot better-armed, and equipped with a lot more social permission to brutally and violently haze the young man to see if he was sufficiently committed to be admitted to the society of fully adult men. But today, safeguarding of all kinds seems to be being thrown out the window.

Meanwhile, the team play for young men has only grown more accommodating and supportive. To quote a very articulate incarcerated man, “Nobody ends up in maximum security by accident. Every guy in here is here for the same reason as me: he likes really weird stuff.” One of the features of modern male solidarity is that, unlike the puritanical male solidarity of 18th-century duels and desperate escapes from girls’ bedroom windows that existed to enable penetrative, reproductive sex, today’s male solidarity is an “all-in” kind of solidarity, the solidarity that retroactively stands behind whatever you did to that hooker.

~~~

Since the rise of “female impersonators” during the Interwar years, “drag queens” and “transsexuals” have been a part of popular culture of which men — even teenage boys — were well-aware. These individuals were same-sex attracted men who, in addition to the many other burdens carried by other gay men, also strongly preferred being with men who understood themselves to be straight, over other same-sex attracted men.

As pretty typical adolescent male shitheads, my friends and I had a lot of homophobic things to say about the gayest, most effeminate gay men. There was an uncomfortable amount of homophobic talk around my D&D table in the 80s (I can’t believe our one gay player is still friends with us — I guess it’s a testament to how even more homophobic everyone else was). And it is no coincidence that as our discourse adapted to the slow-motion revelation that we had gay friends and our whole scene was actually pretty damn gay-adjacent, our insecure masculinity and homophobia came to target those individuals as remaining legitimate targets of our homophobia.

It was not until my 1996 encounter with the late Jamie Lee Hamilton, a feminist transgender organizer in Vancouver, that I came to fully humanize these most effeminate men and begin to work as an ally of the transgender community. Back then, of course, there was a normative “trans woman”: an often-racialized male sex worker who was exclusively attracted to “straight” rather than other gay men. It seemed only reasonable to include this community in the larger complex of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people seeking out rights and respect. They were, back then, a tiny minority in that minority community of minorities.

But by this time, I was a cultural and political outlier. There was no embrace of these men by geek culture, which remained reflexively homophobic.

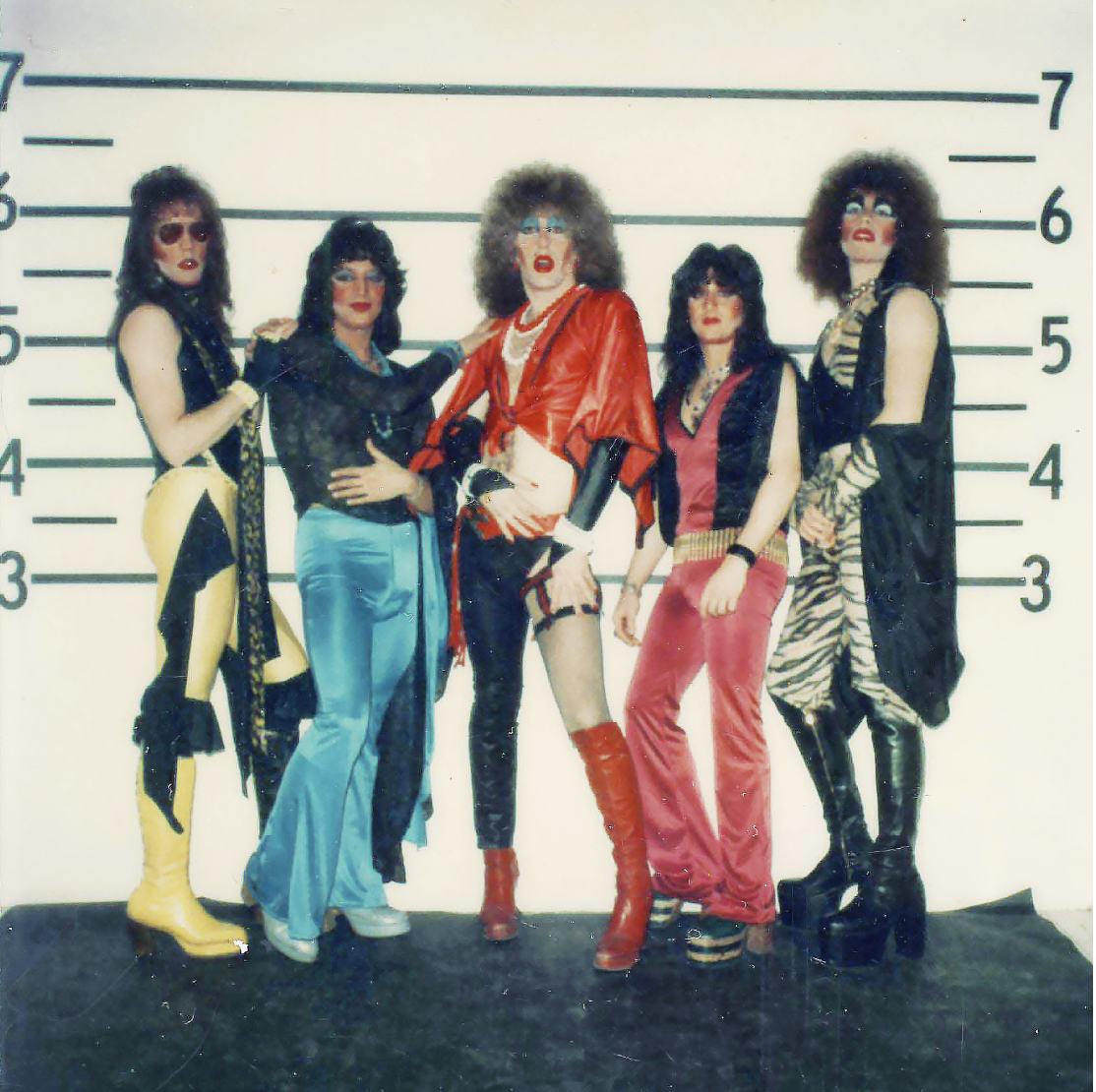

In the 1980s, Jamie Lee’s brothel was not the main thing that was going on with men in skirts. Indeed, the female impersonator, as they were politely called, was wholly eclipsed in the popular imagination when it came to men in skirts. AC/DC, Twisted Sister, and the “hair metal” movement was our generation’s rebuttal to the Regan era’s effort to make patriarchy great again. The on-stage antics of Dee Snyder and his ilk were emblematic of the early music video era.

Clad, usually, in age-inappropriate “girls’” clothes, these men delivered what are best characterized as hypermasculine performances. They were not exhibitions of conventional forms of male domination but were, instead, highly performative, ritualized ways of showing forms of masculinity so transgressive as to be outside of the behaviour a man with unexceptional levels of social power could do.

This is the centre of the hair-metal aesthetic: men exhibiting uniquely and emblematically masculine traits that are so exaggerated they are transgressive. Indeed, the term “masculinity” used to refer specifically and singularly only to this set of behaviours. During the First Gilded Age, “manliness” referred to socially constructive, normative forms of male behaviour to be aspired-to. But beyond the frontiers of the self-controlled family man masculinity of the Victorians was a sick, an unhealthy, an unbridled, savage way of being a man.

The plaid schoolgirl skirt on stage was, in this way, of a piece with the gang rape of intoxicated underaged groupies. The rock-and-roll hair metal lifestyle was the epitome of hypermasculinity, i.e. manliness, minus the self-control. The guitar riffs became less about the sound emanating from the guitar and more about the masturbatory way the lead singer held his proxy oversized phallus. The idea of dressing up in underaged girls’ clothing and simulating masturbation in front of a crowd of thousands of screaming fans is the very essence of unbridled, retrograde, hypermasculinity.

In effect, these artists were engaged in something adjacent to what journalist and author of Trans, Helen Joyce, has described as a “contactless sex crime” — the conscription of strangers, without their consent, into exhibitionist, masturbatory self-gratification. But hair metal artists obtained their audience’s consent. There was no conscription, only the spectacle.

So, why were the main fans of this kind of musical performance straight men? Some men of my generation simply loved this music because they aspired to be that profane exhibitionist hair metal star, in the same way they might (likely concurrently) aspire to be the dead-eyed, post-operative porn star in the Penthouse “lesbian” pictorial. There was a deeper solidarity there: the idea that a man who could get away with being hypermasculine deserved our loyalty and should be celebrated as a man living out extreme forms of behaviour they never would by themselves.

Especially important to this kind of admiration — this kind of perverse hero-worship was its episodic and temporally finite nature. Every man has the right to fully indulge his most deranged and extreme masculine traits in one special context, according to a conventional scheme of patriarchal values. These men were leading the way, and none of us had to dispose of the body of a dead sex worker at the end of the night.

You see, the “dead hooker” oath is about verbalizing an unspoken covenant amongst men, a crucial part of our sex-based solidarity. In this social contract, every guy “has their thing” — that “really weird stuff” he likes. Men don’t necessarily want to know what their friend’s dark fetishistic acts and desires are, but we do feel a shared obligation to cover for that guy when he gets in trouble because of it, on the expectation that millions of men all around us will do the same for us when our time comes. The Hulk did not just remind us to cheer for Lou Ferigno’s rage-out as Banner’s alter-ego at the crescendo of the story, it also told us to shed a wistful tear for Bill Bixby having to pack up and leave town again just because he got a little too carried away.

I want to suggest that from the “womanface” drag queen-informed performances of trans womanhood we saw from same sex-attracted men who preferred straight men even a decade ago, we have, over the past 10 years, remade our vision of normative transwomanhood into the heterosexual, exhibitionistic, autoerotic, pedophilia-inflected, rage-filled, screaming, shouting, misogynistic performances of the worst of 80s hair metal.

We GenX men are the enablers of our contemporaries turning their lives into an endless, conscriptive sex LARP, in which everyone must pretend that the guy acting like the headliner of a gnarlier AC/DC cover band is actually the porn star from the Penthouse spread. And anyone who doesn’t go along is breaching the “dead hooker oath.” We are supposed to cover for the gnarliest, rapiest dudes while secretly admiring their ability to embrace a completely phallocentric life, to become, like the Hulk, their own hypermasculine superman.

There are two popular chants associated with this work: “trans women are women” and, more honestly, “some women have penises.” Of course, none of us recognizes these shouty, belligerent, angry men as women. Their social power, their social license, comes from the male solidarity they enjoy precisely because no one sees them as women.

Stuart Parker is a Vancouver-based writer and broadcaster, who serves as president of Los Altos Institute, an eco-socialist think tank. He has previously served as leader of the BC Green Party and as a lecturer at Simon Fraser.