Last month, American actress Susan Sarandon tweeted, “SEX WORK IS WORK!” alongside a CNN article about a new art exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London entitled, “Decriminalized Futures.” The exhibit, running from February 16-May 22, posits:

“Full decriminalization of sex work is the rallying cry that unites the sex worker rights movement across the world. Under this banner, sex workers and their allies have fought tirelessly for strong workers’ rights, an end to exploitation, an end to criminalization, and real measures to address poverty.

Decriminalized Futures is a celebration of this movement.”

Despite Sarandon’s tweet getting roughly 1,900 likes, it also attracted responses from women expressing disappointment in the Thelma & Louise star, as well as a sense of betrayal. They pointed out that prostitution is sexual exploitation and reminded her that the industry is host to pervasive violence, sexually transmitted diseases, as well as high addiction and suicide rates. Women asked Sarandon questions like, “If it’s work why are women and girls trafficked into it?” “Will you be encouraging your daughters, sisters, nieces, friends, aunts, mom, etc, to go into this ‘work’?” “When did you last sell yourself for money?” One user told her, “Our vaginas are not a work tool!”

For years, feminists and survivors of prostitution have insisted that sex is not work, that the sex trade is inherently exploitative, and that women are victims in this industry.

The CNN article Sarandon shared alongside her tweet referenced depictions of prostituted women in film which contribute to the normalization of women as exploitable, as well as to misconceptions about the sex industry.

The co-curator of “Decriminalized Futures,“ Elio Sea, tells CNN that Pretty Woman (1990) is “a great film,” though she is critical of the “rags to riches (story)” which sees Vivian (played by Julia Roberts) “saved by this man who’s her client.” She adds, “If you look at it from a feminist angle and you look at it from a sex worker rights angle, it’s not great.” Sea is correct that the “prince saviour” narrative is “not great.” The popularity of the film likely played a significant role in warping young women’s perceptions of the sex trade and exit strategies. Pretty Woman is probably the most popular Hollywood feature film about a prostituted woman ever, having made over US$432 million at the worldwide box office. By comparison, Moulin Rouge! (2001) and Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) — two other mainstream movies about prostituted women — “only” made US$179 million and US$161 million, respectively.

These three films are set in various times and places throughout the world and history, but share commonalities: the lead females were driven into prostitution by poverty and are unhappy about prostituting themselves. Pretty Woman and Memoirs of a Geisha incorporate a Cinderella narrative, wherein a rich man is presented as the solution to their predicament. In the former, Edward — a cultured millionaire businessman played by Richard Gere — is the “prince,” who saves Vivian from prostitution. In the latter, Ken Watanabe plays the wealthy businessman who saves Ziyi Zhang’s character from prostituting herself to survive. Satine, the character played by Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge!, prefers a penniless writer to the rich duke who wants exclusive sexual rights to her — he has Satine’s pimp sign a contract to this effect. All three films normalize men’s sexual exploitation of women as the natural order of things, as well as women selling themselves to men/men buying women.

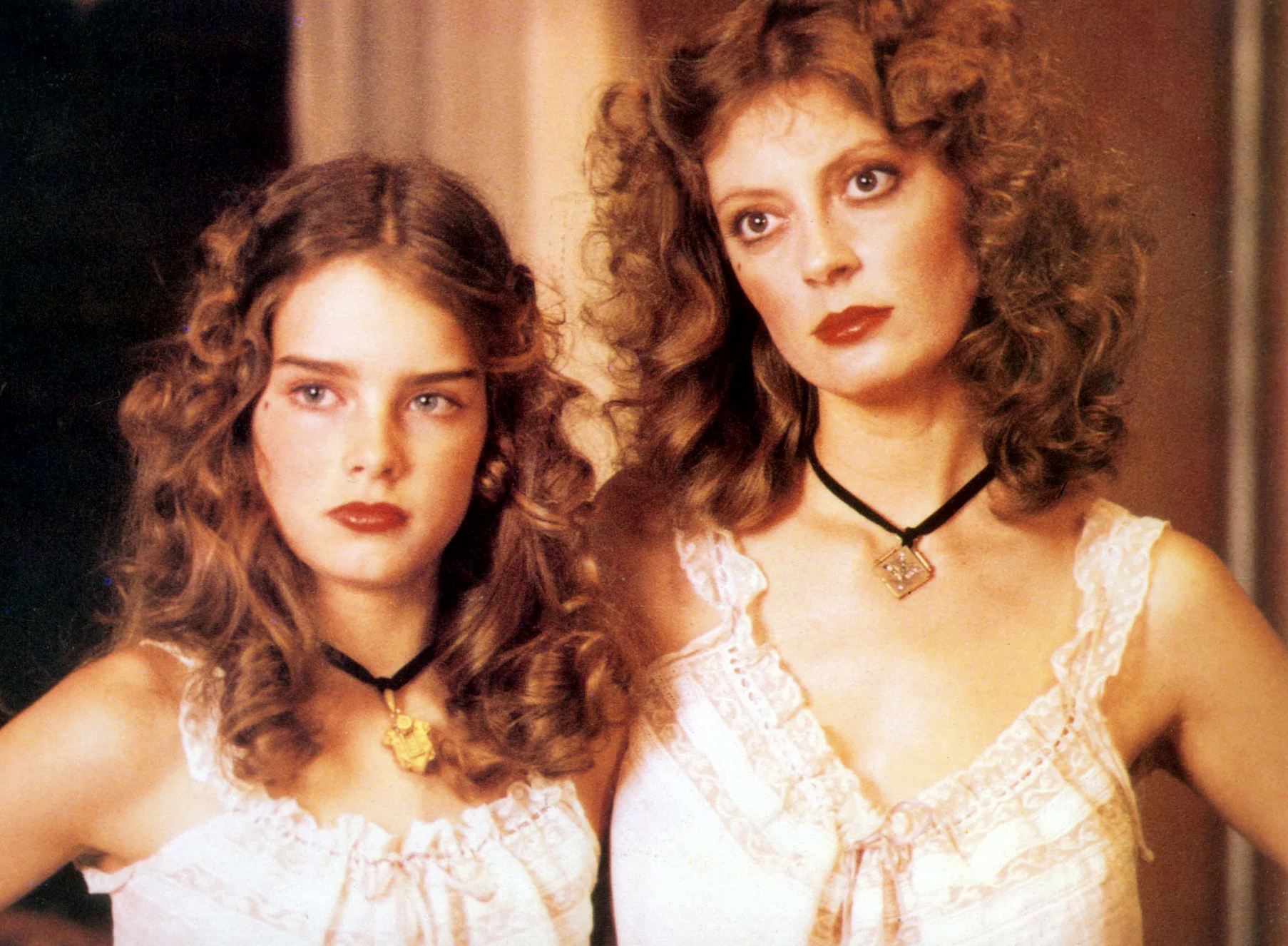

While these films are among the most well known, Hollywood movies are rife with prostituted women. “Prostitute” is a common occupation for female characters, and Hollywood has accustomed viewers to seeing women — even girls — as prostitutes. In the 1930s Baby Burlesk comedy shorts, wherein toddlers play the roles of adults, Shirley Temple plays a prostitute/burlesque dancer/call girl. Polly Tix in Washington has Temple sashaying into a room bare-legged, suggestively telling a little boy she was sent to entertain him before planting a big kiss on him, warning, “I’m expensive.” She appears to be a call girl, sent by a second boy to convince the first boy to do his bidding. In 1978, Brooke Shields plays 12-year-old Violet, the daughter of a prostitute (played by Sarandon) working in a New Orleans brothel, who is auctioned off by the madam to the highest bidder for her virginity. At 12 years old, Jodie Foster was cast in the role of Iris in the 1976 film, Taxi Driver, as a runaway and “child prostitute” befriended by a mentally unstable taxi driver/Vietnam war veteran (Robert De Niro) who kills her pimp (Harvey Keitel) to save her from prostitution. Beyond the famous central characters are the numerous unknown girls who have played prostitutes in various films, like the ones in Memoirs of a Geisha.

Prostituted women feature in many more films over decades: Carole Lombard played Mae in the 1932 film, Virtue; Vivien Leigh was cast in the role of Myra in Waterloo Bridge in 1940; Susan Hayward portrayed Barbara Graham as a prostitute in the 1958 film, I Want to Live; Elizabeth Taylor played high end call girl, Gloria Wandrous, in Butterfield 8; Jane Fonda was cast as the New York City prostitute in the 1970 film, Klute, who says to her psychiatrist, “For an hour, I’m the best actress in the world. I’m the best fuck in the world.” Rebecca De Mornay plays the prostitute who assists a high school student (Tom Cruise) in turning his parents’ house into a brothel for one night in Risky Business (1983); Kim Basinger played a high end prostitute in L.A. Confidential (1997); in Chloe, a woman played by Julianne Moore hires an escort (Amanda Seyfried) to test her husband’s faithfulness; and Penélope Cruz plays “Anna,” a prostitute mistakenly sent to the room of a newlywed man, who then pretends to be his wife to impress his family in 2012’s To Rome With Love. Susan Hayward, Elizabeth Taylor, Jane Fonda, and Kim Basinger all won Best Actress in a Leading Role or Best Actress in a Supporting Role Oscars for these portrayals.

Prostituted women are not only leading characters in film, but part of the scenery. From The Wolf of Wall Street to Blade Runner: 2049, to The Favourite — as well as PG-rated movies like Big, Hook, and Beetlejuice — prostitutes are ubiquitous. In the 1988 film, Big, the first women to speak to Tom Hanks in New York are prostitutes who ask, “You lookin’ for a little fun tonight?” In Hook, starring Robin Williams, Julia Roberts, and Dustin Hoffman, some of the only women in Neverland are four prostitutes, while males feature prominently, as pirates and the Lost Boys. Tim Burton’s fantasy comedy Beetlejuice includes a whorehouse called Dante’s Inferno Room, in which five prostitutes beckon Michael Keaton from balconies advertising “GIRLS,” before he enters the brothel. The further back you look, the subtler these inclusions tend to be. For example, in It’s a Wonderful Life, James Stewart runs past a “strip tease bar.” Lolita, played by Sue Lyon in the 1962 film version of the book, Lolita, is sent to a camp called, “Camp Climax for Girls.”

Just as Hollywood has accustomed us to seeing women as prostitutes, it has accustomed us to seeing men as natural leaders. Few actresses have portrayed the President of the United States in a Hollywood movie: Charlize Theron only becomes President at the very end of Long Shot (2019); Glenn Close very briefly plays acting President in 1997’s Air Force One; and Sela Ward plays the President in the 2016 sci-fi blockbuster Independence Day: Resurgence. Men, on the other hand, are routinely cast as in the role — I was able to come up with a list of 23 men who portrayed a fictional President of the United States between 2000 and 2017, from Jeff Bridges in The Contender (2000) to Andy Garcia in Geostorm (2017), and this likely isn’t even a full list. Conversely, there haven’t been many Hollywood feature films about male prostitutes. Only Midnight Cowboy (1969) and My Own Private Idaho (1991) come readily to mind.

While one might argue these are merely depictions of reality, movies provide space to create a fantasy land that filmmakers can populate according to their wishes. They choose to regularly depict women as prostitutes but could just as easily decide to depict them in positions of power. Movieland is the perfect place to explore and normalize the idea of powerful women in roles like presidents, judges, CEOs, etc. Portrayals of female presidents would help normalize the idea in the minds of American voters, who thus far have shown themselves averse to electing a woman to this position.

All this reminds me of Vivian’s line in Pretty Woman: “People put you down enough you start to believe it… The bad stuff is easier to believe.” When the world’s most popular films portray women as prostitutes and men as world leaders, it’s not inconceivable that viewers will begin to believe this is the natural order of things. “If she can see it, she can be it,” is the tagline attached to Geena Davis’ Institute on Gender in Media — notable, considering she was Sarandon’s co-star in Thelma & Louise.

One reason for the pervasiveness of prostituted women in Hollywood cinema may be that filmmakers, who have predominantly been men, see women generally as sexually exploitable. They clearly enjoy seeing prostituted female characters, but filmmakers also know these depictions will appeal to male audiences, offering them something titilating and objectifiable. Sex sells, making money for mostly male-owned production companies.

Women, on the other hand, are less keen to be commodified and sexually exploited by men. Most women are aware of the precariousness and suffering inherent in the lives of prostituted women, and can imagine that sex with strange men is undesirable as a career choice. Unfortunately, due in part to the way prostitution narratives in media have warped women and even girls’ perceptions of prostitution, a growing number of women and girls now appear to believe that sexual exploitation can be a legitimate and even enjoyable form of work. Perhaps they have bought the oft-conveyed idea that a female’s worth is tied to the amount of money a man will pay for her. Twenty-odd years ago, Nicole Kidman chastised Jim Broadbent for holding that view in Moulin Rouge!, saying to him, “All my life you’ve made me believe I was only worth what someone would pay for me.”

Given the way Hollywood has accustomed us to seeing women as prostitutes, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that a Hollywood actress espouses the mantra, “Sex work is work.”

Alline Cormier is a Canadian film analyst and retired court interpreter with a B.A. Translation from Université Laval. In her second career she turns the text analysis skills she acquired in university studying translation and literature to film. She makes her home in British Columbia and is currently seeking a publisher for her film guide for women.